This piece was originally published in the 2015 Super Mobility Week Official Show Daily.

Over the last eight years, we have seen a remarkable surge in American mobile competition. LTE, the dominant 4G technology, has been a boon to the U.S. mobile sector due to its early, mass adoption ahead of nearly every other country in the world. Consumer services and devices fueled by 4G LTE have been a Cinderella American success story. While 2G and 3G have been viewed as European and Japanese success stories, now America has become the envy of the wireless world. Almost no smartphone operates without Apple or Google technology, and an entirely new branch of the economy – the “app economy” – has been created in the few years since smartphones got really smart and much faster, leading to billions in sales, job creation and economic growth.

This may all change again with 5G. Typically, we have a generational shift in wireless network technology every seven years. The first 4G LTE network was launched by Verizon Wireless in 2010 so the timing is ripe for another technology upgrade. So, is it a coincidence this generational shift is a topic of discussion once again – whether we’re ready or not?

We are all seeing the capabilities but also the practical limits of LTE and are coming to the realization that we need something else, something more, to satisfy the demands of the future. And, the same way that every other generational shift has reshuffled the competitive positioning of carriers and countries alike, the sweet rewards of success will come to those who most quickly can exploit the new opportunities 5G presents to both operators and device-makers. Considering that the U.S. has been so successful in 4G, the negative consequences of being ill-prepared for 5G would be especially severe, and the onus of stepping up lies on operators and regulators alike.

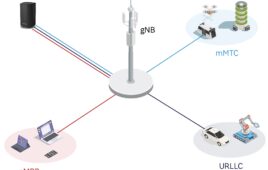

So how prepared is the U.S. today to meet the 5G goal of 100 billion connected devices, 10 Gigabit speeds and less than 1 millisecond latency?

Operators and vendors are tackling the challenge of connecting 100 billion devices and less than 1 millisecond latency through solutions such as network function virtualization and software-defined radios that achieve greater computational power and allow operators to provide more services and applications more efficiently and cost effectively to more users. American operators such as AT&T and Verizon are among the handful of operators around the world to test and commit to deploying these new technologies.

The industry can also utilize existing spectrum more effectively using a new modulation scheme and more cell site splitting, but that will only get us to part of the distance. Historically every new generation of wireless technology with a new modulation provided us with a five-fold increase in speed. But will U.S. spectrum policy undercut the potential speed increases?

In order to achieve optimal 5G speeds across scale networks, U.S. operators need more spectrum in larger contiguous blocks; however, this is not the path the FCC looks to be pursuing even while its global counterparts are. As part of the FCC’s National Broadband Plan, President Obama promised to identify 500 MHz of new spectrum for wireless broadband networks over a 10-year period. To its credit the FCC has taken steps to meet the plan’s goals for spectrum allocation. The agency concluded the highly-successful AWS-3 auction and is preparing to hold the broadcast incentive auction expected to take place in 2016. But will this be enough and can the incentive auction provide the spectrum building blocks needed for 5G?

The incentive auction is the last block of publically-identified spectrum that is part of President Obama’s promise to allocate 500 MHz of additional spectrum for commercial mobile broadband services over ten years. Five years into the promise, 115 MHz have been brought to market through the AWS-3, AWS-4 and PCS H-Block auctions. And if the broadcast incentive auctions occur next year, the total increases up to another 120 MHz. This leaves US operators 265 to 385 MHz shy of the 500 MHz goal. According to CTIA, the wireless industry needs at least another 350 MHz deployed by the end of the decade to keep pace with current growth projections. Considering that six years is the shortest time period between the FCC identifying a band of spectrum for commercial use and when the spectrum can actually be deployed, the prospect of seeing the equivalent of four new bands of spectrum being ready to deploy in the next five years is daunting if not impossible to imagine. Especially when we consider that the initial 115 to 235 MHz most industry experts see as viable are the low-hanging fruit that were known candidates before the 500 MHz goal was announced. Thus, any additional bands needed to meet the 500 MHz goal will be extremely difficult to pry loose from existing users.

If and when new spectrum becomes available and we want to achieve the best possible speeds, then we need to license the spectrum in large contiguous channels. The reason why many operators in Europe can offer faster wireless download speeds compared to their U.S. counterparts is that the European carriers have 20×20 MHz channels available, which is difficult, if not impossible, for their U.S. peers to achieve. If the FCC continues to license 5×5 MHz or at a maximum 10×10 MHz channels and some of them with known interference characteristics, it would be hypocritical to blame the industry for not being able to provide the fastest speeds on earth when they were not given the spectrum to actually do the job in addition to serving more customers per MHz licensed than in any other G7 country.

Furthermore, the U.S. must continue on its path of technology agnosticism for the use of wireless spectrum. Staying above the technology fray and refusing to dictate specific technical parameters for U.S. mobile operators has turned out to be one of the most august decisions that the FCC has ever made. Innovators and the unforgiving nature of the consumer-driven mobile marketplace in the US has proven far more adept at driving the optimal technology solutions than regulatory fiat. But this is all about future allocations. What do operators do right now to stay ahead of the race to 5G?

Clearly the operators have to maximize the spectrum and infrastructure assets available to them today. Efforts like LTE-U and LTE-AA are underway and are intended to expand spectrum solutions using both licensed and unlicensed spectrum. WiFi continues to proliferate while small cell and fiber deployment are happening in parallel tracks. All signs indicate the industry – operators, infrastructure vendors,

chipset makers and technology innovators – are doing everything they can to extract every ounce of spectrum utility from current allocations. But, as we know that won’t be the full solution. It will only delay a crunch and a pause on the path to 5G until the U.S. government makes more spectrum, in wider channelizations available.

The game is afoot and there is much good news but it will only last as long as the regulator continues pushing to get more spectrum freed up for commercial mobile use.