Internet-connected cars are not only a consistent trend in the automotive space, they also carry a security risk. This begs the question, how will a large-scale hack targeting automated cars affect the flow of an urban environment, like the streets of Manhattan?

Skanda Vivek, postdoctoral researcher in the Peter Yunker lab at the Georgia Institute of Technology, and his team will present their answer to that question at the 2019 American Physical Society March Meeting in Boston. Although individual collisions have reached the public eye, this work quantifies how hacked self-driving cars will affect traffic flow.

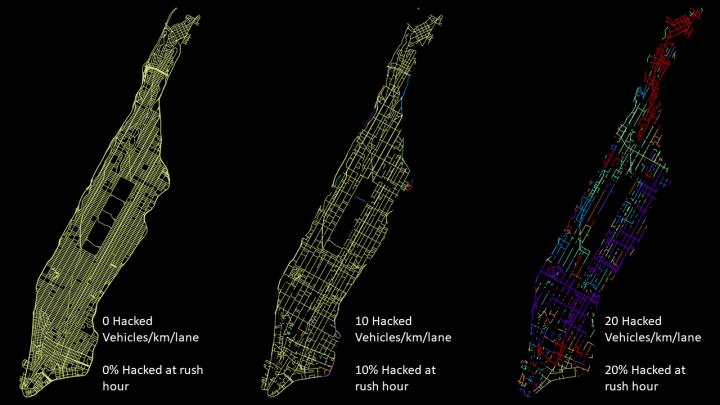

Their findings suggest that just a small-scale offensive (reaching 10 percent of cars in Manhattan) could have severe side effects—a citywide gridlock that puts commuters and emergency vehicles at a standstill.

The team used percolation theory to make their model, which is “a mathematical approach based on the statistical analysis of networks,” according to American Physical Society.

In addition to predicting the negative waves compromised vehicles would unleash upon New York City, the researchers also devised a risk-mitigation strategy. Their proposed strategy, according to American Physical Society, consist of “using multiple networks for connected vehicles to decrease the number of cars that could be compromised in a single intrusion.”

“If no more than, say, 5 percent of connected vehicles were compartmentalized to the same network or utilized the same network protocols, the chance of citywide fragmentation would be low,” says Vivek. “Therefore, a hacker with the intention of causing large-scale disruption faced with this compartmentalized multi-network architecture would be required to execute multiple simultaneous intrusions, which increases the difficulty of such an attack and makes it less likely to occur.”

Vivek continues by highlighting the importance of these findings, explaining that “compromised vehicles are unlike compromised data. Collisions caused by compromised vehicles present physical danger to the vehicle’s occupants, and these disturbances would potentially have broad implications for overall traffic flow.”

“Connected cars are the future,” explains Vivek. “They hold tremendous potential for positive impact economically, environmentally, and, for former drivers no longer frustrated by congested commutes, psychologically. Our work is not in opposition to the future of connected cars. Rather, the novelty of our work lies in identifying and quantifying the underlying cyber-physical risks when multiple connected vehicles are compromised. By shining a light on these technologies at an early stage, we hope we can help prevent worst-case-scenarios.”

In the image below, you can see how hacks can affect the traffic flow in Manhattan, where roads of the same color denote they are part of the same cluster, in other words, they are connected. With everything running as usual (far left), all roads are connected and flowing normally. When 10-20 percent are hacked during rush hour (middle, far right) , the size of the largest cluster reduces drastically. According to the researchers, “We call this threshold (~10-15 hacked vehicles/km/lane) the point of city fragmentation. Essentially half the city is inaccessible from the rest above this threshold.”

(Image Source: Skanda Vivek/ Georgia Tech)