It is a fact universally acknowledged that a smartphone in possession of Wi-Fi must be in want of more power.

Wi-Fi enables us to stay connected without cell service, sparing many a millennial the dreaded text from mom, reminding us that we’ve already used most of our data for the month. (This is usually preceded by the forwarded text alert from the wireless carrier.)

Wi-Fi, however, consumes a lot of energy. Before we know it, we can’t even text mom an apology because our phone just died in-between deleting an email and checking our bank account.

But that could soon change.

University of Washington computer scientists and electrical engineers have successfully generated Wi-Fi transmissions using 10,000 times less power than existing Wi-Fi chipsets and 1,000 less power than other wireless communications platforms, such as Bluetooth LE and ZigBee. This new “Passive Wi-Fi” transmits signals at bit rates up to 11 megabits per second and can be decoded on any Wi-Fi device (including routers, smartphones, and tablets) over distances of 30 to 100 feet.

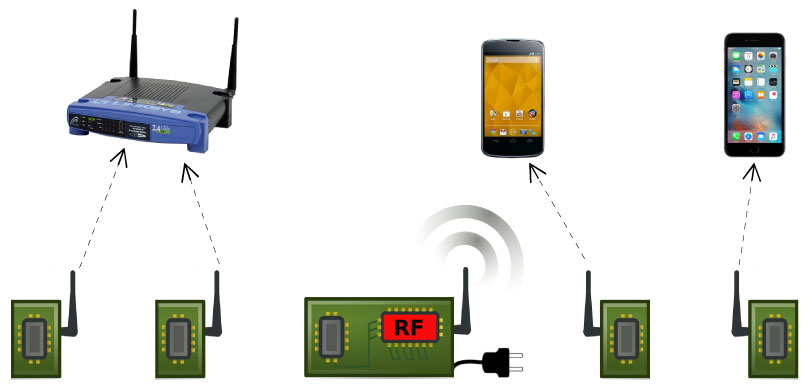

To achieve this, the team decoupled the digital and analog operations, the latter of which still consume a lot of power. The system architecture assigns the analog functions to a single, plugged-in device that generates a continuous wave of RF signal.

Instead of every device having digital and analog RF, now only a second, passive device has digital baseband. A processor on this passive device selectively reflects the RF signal to generate Wi-Fi packets that are then decoded on existing devices—a process that synthesizes only 15 to 60 µW of power.

In Passive Wi-Fi, power-intensive functions are handled by a single device plugged into the wall. Passive sensors use almost no energy to communicate with devices. (Image courtesy of University of Washington)

“All the networking, heavy-lifting and power-consuming pieces are done by the one plugged-in device,” said Vamsi Talla, electrical engineering doctoral student. “The passive devices are only reflecting to generate the Wi-Fi packets, which is a really energy-efficient way to communicate.”

“Even though so many homes already have Wi-Fi, it hasn’t been the best choice for that,” added Joshua Smith, UW associate professor of computer science and engineering and of electrical engineering. “Now that we can achieve Wi-Fi for tens of microwatts of power and can do much better than both Bluetooth and ZigBee, you could now imagine using Wi-Fi for everything.”

The researchers will present their findings (considered one of 10 breakthrough technologies of 2016, according to MIT Technology Review) at the 13th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation next March.