The Copernicus Sentinel-1 radar mission shows how cracks cutting across Antarctica’s Brunt ice shelf are on course to truncate the shelf and release an iceberg about the size of Greater London – it’s just a matter of time.

The Brunt ice shelf is an area of floating ice bordering the Coats Land coast in the Weddell Sea sector of Antarctica.

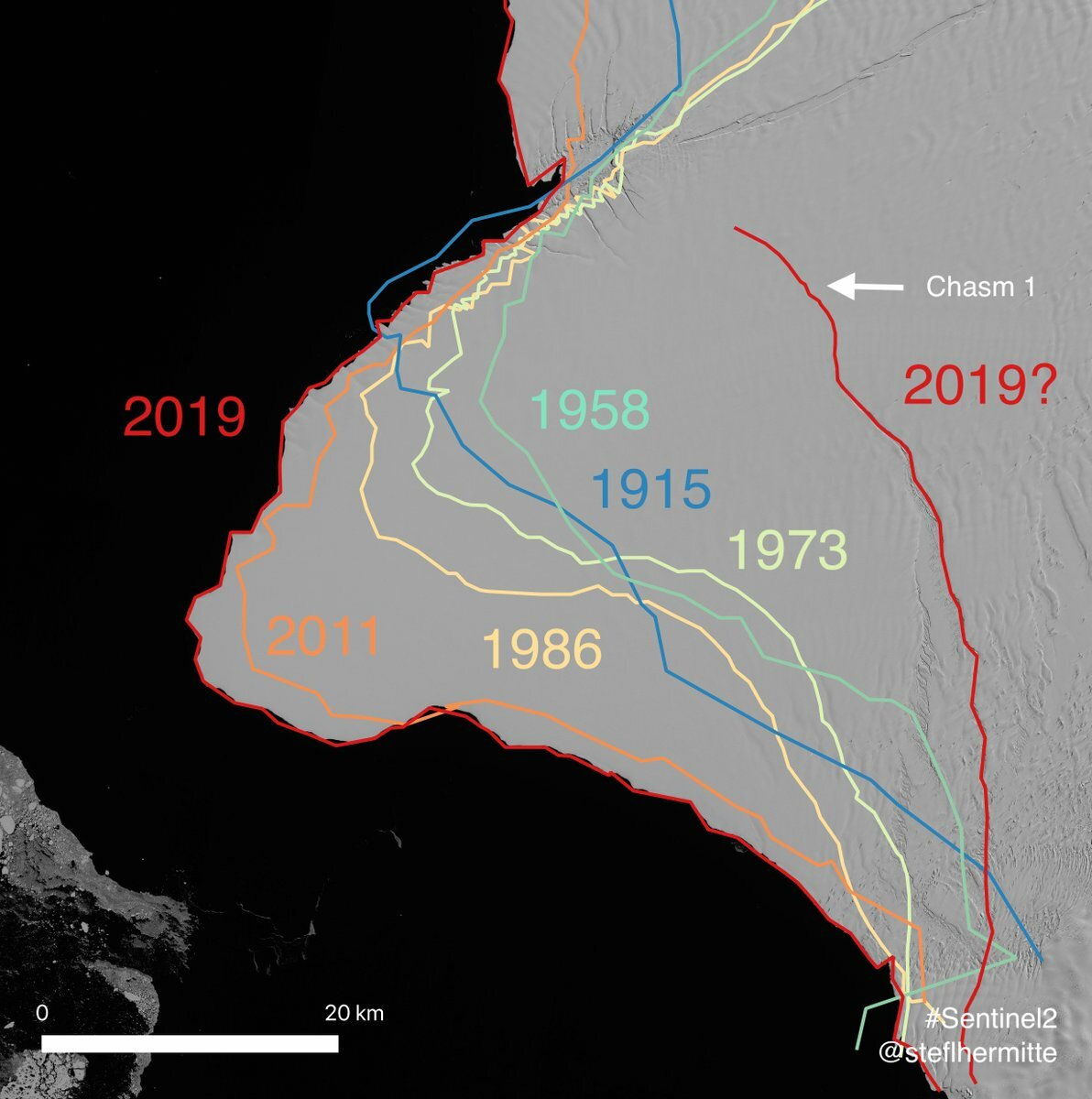

Figure 1: Comparison of Brunt ice shelf calving front locations over the last 100 years, based on 1915 and 1958 historical survey data from the Endurance expedition (Worsley 1921) and International Geophysical Year, respectively, followed by the location in satellite images from Landsat in 1973 and 1978, ESA’s Envisat in 2011, and Copernicus Sentinel-1 in 2019. Comparison of the images indicates that the Brunt ice shelf is at its maximum 20th Century extent. (Image Source: contains modified Copernicus Sentinel-2 data (2019), courtesy Stef l’Hermitte TU Delft)

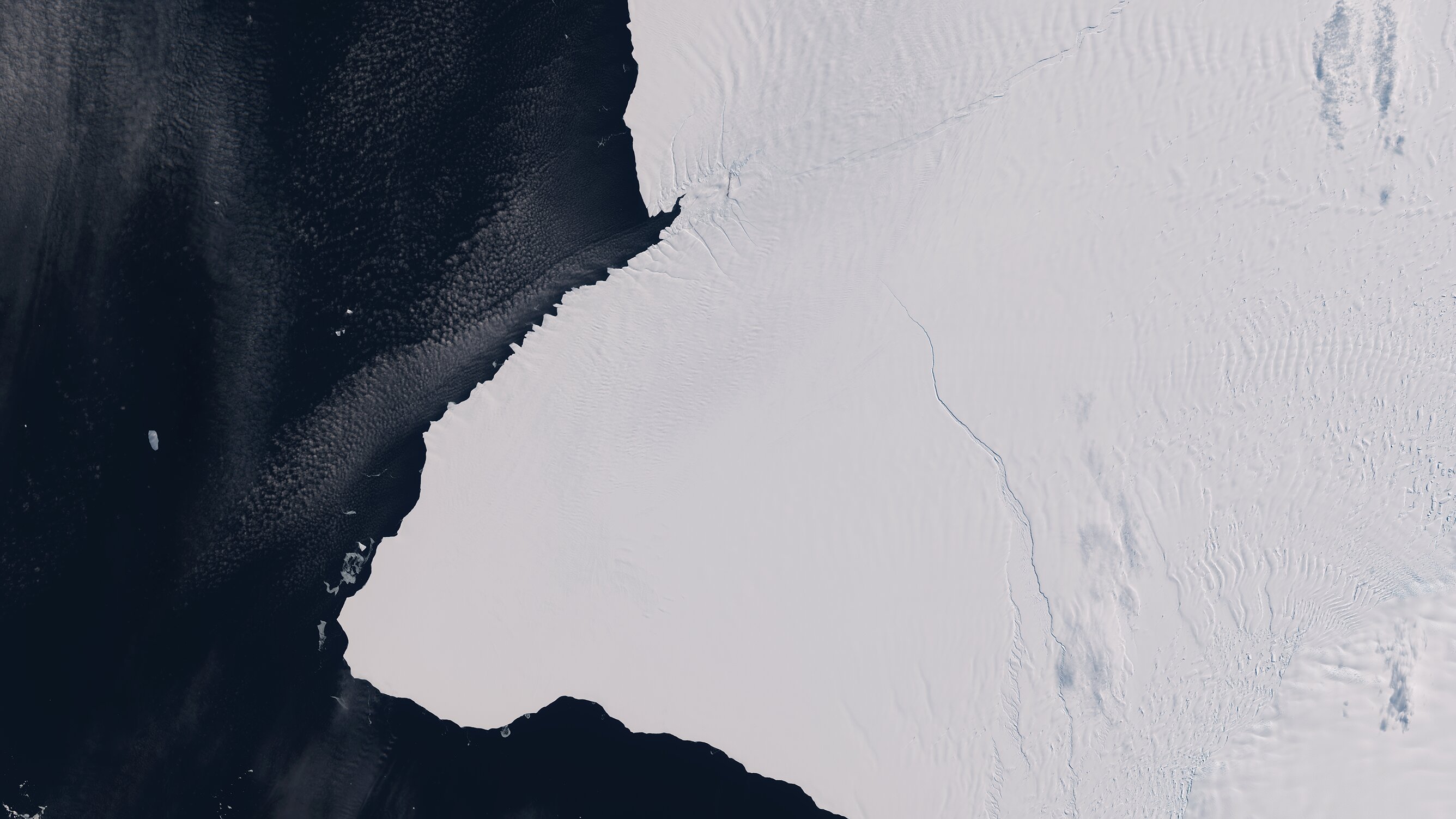

Using radar images from the Copernicus Sentinel-1 mission the animation shows two lengthening fractures: a large chasm running northwards and a split, dubbed Halloween Crack, that has been extending eastwards since October 2016. They are now only separated by a few kilometres.

Halloween Crack runs from an area known as McDonald Ice Rumples, which is where the underside of the otherwise floating ice sheet is grounded on the shallow seabed. This pinning point slows the flow of ice and crumples the ice surface into waves.

Brunt ice shelf is at its maximum extent during the satellite era and compared to images collected by Argon declassified intelligence satellite photographs in 1963 and maps made by Frank Worsley during the Endurance expedition into the Weddell Sea in 1915.

History shows that the last event was in 1971 when a portion of ice calved north of the Ice Rumples and in what appears to have been a previous iteration of today’s Halloween Crack which is separating along lines of weakness.

Mark Drinkwater, Head of ESA’s Earth and Mission Science Division, says, “Importantly, tracking the entire ice shelf movement reveals a lot going on north of the Halloween Crack, where the shelf flows in a more northerly direction. Meanwhile, this divergence is splitting the northern and southern parts of the shelf along the Halloween Crack.

“Interestingly, the animation also reveals a widening split right across the Ice Rumples, which may also put the structural integrity of this northern outer segment into question.

“We have been observing the Brunt ice shelf for decades and it is constantly changing. Early maps made in the 1970s indicate that the ice shelf was more like a mass of small icebergs welded together by sea ice.”

As the ice flows down the steep coastal area and across the grounding line into the floating ice shelf, it fractures into a series of regular blocks. The structural integrity of the shelf relies on the fractures being filled over decades by marine ice and snow. Since Copernicus Sentinel-1 radar penetrates through the surface snow, this pattern of fractures is revealed to give Brunt its skeletal-like appearance.

When the chasm and cracks around McDonald ice rumples finally intersect, it is likely that the northern end of the calved iceberg remains pinned by its grounding point, leaving the southern end of the berg to swing out into the ocean.

Although it may be the biggest berg observed to break off Brunt, compared to the recent Larsen ice shelf iceberg A68, for example, it won’t be a particularly large. However, the concern is that this calving could allow the ice left behind to flow more freely towards the ocean.

This Copernicus Sentinel-2 image from 7 February 2019 shows two lengthening fractures: a large chasm running northwards and a split, dubbed Halloween Crack, that has been extending eastwards since October 2016. They are now only separated by a few kilometres. Halloween Crack runs from an area known as McDonald Ice Rumples, which is where the underside of the otherwise floating ice sheet is grounded on the shallow seabed. This pinning point slows the flow of ice and crumples the ice surface into waves. Routine monitoring by satellites with different observing capabilities offer unprecedented views of events happening in remote regions like Antarctica, and how ice shelves manage to retain their structural integrity in response to changes in ice dynamics, air and ocean temperatures. (Image Source: Contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2019), processed by ESA, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO)

“We are now poised for this eventual calving, which could have consequences for the ice shelf as a whole. After the 1971 calving, ice shelf velocities are reported to have doubled from 1 to 2 metres a day. So we will be carefully monitoring the ice shelf with the combination of both Copernicus Sentinel-1 and Copernicus Sentinel-2, which carries an optical instrument, to see how the dynamics influence the integrity of the remaining ice sheet,” continues Dr. Drinkwater.

With the ice shelf currently deemed unsafe, the British Antarctic Survey has closed up their Halley VI research station, which was repositioned south of Halloween Crack and east of the chasm in 2017.

The station used to be operational all year round, but this is the third winter running that it has had to close because of potential danger.

There has been a permanent research station on Brunt since the late 1950s, but in 2016–17 the base was dragged 23 km to its current, more secure location. If it had not been moved, it would now be on the seaward side of the chasm.

Routine monitoring by satellites with different observing capabilities offer unprecedented views of events happening in remote regions like Antarctica, and how ice shelves manage to retain their structural integrity in response to changes in ice dynamics, air and ocean temperatures.

The Copernicus Sentinel-1 mission carries radar, which can return images regardless of day or night and this allows us year-round viewing, which is especially important through the long, dark, austral winter months. A recent image from the Copernicus Sentinel-2 mission provides complementary information.