A pair of researchers, one with the Langevin Institute, the other a company called Greenerwave, both in France, has developed a way to use ordinary Wi-Fi signals to perform analog, wave-based computations. In their paper published in the journal Physical Review X, Philipp del Hougne and Geoffroy Lerosey describe their experiments and what they represent.

Computers represent information digitally, in ones and zeroes—but back in the early days of computing, there was discussion regarding the possibility of using analog processors. Even then, it was clear that such an approach would be less energy-intensive. But digital won out, and the rest is history. But that might not be the end of the story. As hardware engineers begin to run headlong into the limitations of Moore’s Law, some engineers have begun to take another look at analog processing.

Analog processors make use of the amplitude in waves found in electronic circuits or in light waves. And instead of brute force crunching, they rely on waveform shaping, which is done with metamaterials. Early work with such materials showed that such processors could be highly efficient at matrix processing. But efforts to use such materials have run into difficulties due to fabrication issues. In this new effort, del Hougne and Lerosey demonstrate that some analog processors can be created via a simpler approach.

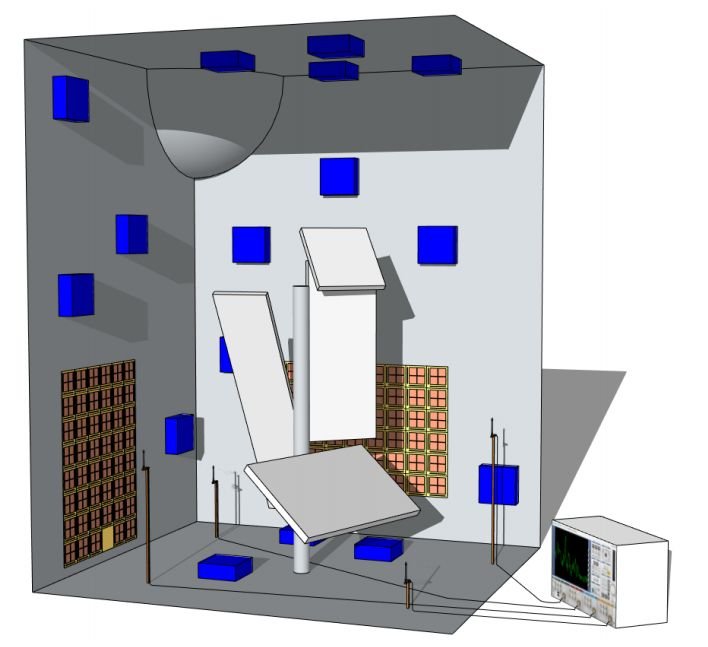

In their experiments, the researchers created a box to simulate a home environment—one with four standard Wi-Fi routers. In the box, they included objects representing furniture and other household items. Next, they applied a panel made of 88 reflector mirrors to two adjacent walls in the box—each of the mirrors was capable of toggling between two states. In one state, the mirror would cause a 0° phase shift, in the other, a 180° phase shift. Finally, the researchers added a control box to run their experiments.

The researchers sent the same standardized signal from all the Wi-Fi routers. They recorded multiple panel configurations to prime the system—doing so allowed them to characterize the scattering of the Wi-Fi signals and then to program the system to perform linear operations. And that allowed them to carry out a four-element Fourier transform.

The researchers report that the processing was faster than it would have been using a digital computer, but was slowed by the initiation process. They suggest that adding as few as 30 inputs to such a system would make it more efficient than a digital system.

Laboratory setup to test feasibility of analog computation with Wi-Fi waves in an indoor room. Credit: arXiv:1804.03860 [physics.class-ph]