A wireless leak detection system created by University of Maine researchers is scheduled to board a SpaceX rocket bound for the International Space Station this summer.

The prototype, which was tested in the university’s inflatable lunar habitat and Wireless Sensing Laboratory (WiSe-Net Lab), could lead to increased safety on the ISS and other space activities.

This is the first hardware from UMaine in recent history that is expected to function in space for a long period of time, according to the researchers.

In advance of the Aug. 1 launch, UMaine researchers are working with NASA to prepare three of the wireless leak detector boxes for flight.

From April 18–20, electrical engineering graduate students Casey Clark and Lonnie Labonte will test the payload, perform an electromagnetic interference (EMI) test, and complete the Phase 2 safety review of the prototype at NASA Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas.

The project was one of five in the nation to receive funding from NASA–EPSCoR for research and technology development onboard ISS.

Ali Abedi, a UMaine professor of electrical and computer engineering, was awarded the three-year, $100,000 NASA grant through the Maine Space Grant Consortium in 2014. Collaborators on the project include Vince Caccese, a UMaine mechanical engineering professor, and George Nelson, director of the ISS Technology Demonstration Office at the NASA Johnson Space Center.

Leaks causing air and heat loss are a major safety concern for astronauts, according to Abedi. It is important to save the air when it comes to space missions—find the leak and fix it before it’s too late.

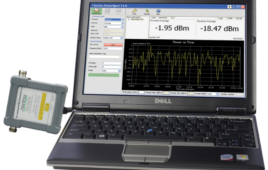

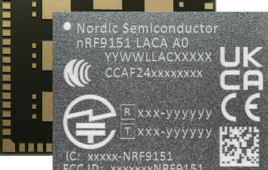

The project involves the development of a flight-ready wireless sensor system that can quickly detect and localize leaks based on ultrasonic sensor array signals. The device has six sensors that detect the frequency generated by the air as it escapes into space and triangulates the location of the leak using a series of algorithms. The device then saves the data on SD cards that are sent back to Earth.

The device is fast, accurate and capable of detecting multiple leaks and localizing them with a lightweight and low-cost system, according to Abedi.

“Our goal is to push the boundaries of hardware and software to design a highly accurate, ultra-low-power and lightweight autonomous leak detection and localization system for ISS,” says Abedi, who directs the WiSe-Net Lab.

Similar systems on the market require astronauts to walk around with a device, scanning walls to detect holes, while the team’s prototype offers a “set-it-and-forget-it” solution, says Clark of Old Town, who graduates in May and will begin work this summer as a ground segment engineer at SpaceX in Hawthorne, California.

“This is the first step in a very progressive movement to monitor structural parameters of spacecraft and the ISS,” says Labonte of Rumford.

The lab prototype was developed from scratch by Clark and Labonte, and includes components that were both created with a 3-D printer and bought off the shelf. Their work followed that of UMaine Ph.D. student Joel Castro and postdoctoral fellow Hossein Roufarshbaf, who developed a leak localization algorithm as part of a previous NASA EPSCoR project.

The additional funding allowed the researchers to make the system more rugged and capable for microgravity environment testing at the NASA Johnson Space Center, and eventually onboard the ISS.

While the devices are in space, astronauts who live in the ISS will install each of the three identical boxes and allow them to collect data for two intervals of about 30 hours, for a total of 60 hours each, according to the researchers.

“While the hardware is in space, our team at UMaine will be on standby mode until data collection is completed,” Clark says. “The system is designed to be automated. So we do not interact with the device during on-board operations.”

After each device collects data, NASA will send the information to the researchers for analysis and processing.

Once the hardware returns to Earth on a re-entry vehicle sometime next year, the team will observe how well the devices survived the launch, deployment and return with the intention of proposing a new design for the next generation, the researchers say.