To be frank, a microwave oven is (at best) no more than a reheating device. The device has been around for over 70 years, and changed very little. In this day and age, it was only a matter of time before the microwave oven would have its time in the innovative spotlight—just not in the way the industry might have hoped. A different method of achieving the same end result could make this longtime reheating method obsolete, and change a lot about how we presently cook and prepare food.

Radio frequency cooking is expected to replace the microwave oven because it’s capable of not only reheating, but cooking food of equivalent quality to a stove or conventional oven. The example used in recent a demo video (shown below) has been a plate of veal, zucchini, and tomatoes—all foods that require different temperatures and durations to be cooked properly. A radio frequency oven or microwave accomplishes this particular facet using precisely controlled high-frequency radio waves. The process not only heats food evenly but retains moisture, unlike microwaves, which can sometimes leave reheated food dry and in varied states of heatedness.

One of the main differences in how this process works compared to microwave ovens is the way both devices generate electromagnetic waves. While microwaves use magnetrons, RF devices use semiconductors. Ideally, RF microwaves containing inverter technology can reduce a 1000-watt microwave by half, resulting in more operational flexibility. Microwave ovens on the other hand, involve turning the same magnetron on and off, which basically uses the same amount of power to reheat food, regardless of how long it’s being used.

According to Dr. Klaus Werner, the most power you’d need is 550 watts. He cited food manufacturers as an example, who he said might be overdoing it with their heating instructions, since they have to make sure any of their frozen meals are thoroughly cooked in any microwave (regardless of power level). RF heating, on the other hand, is so precise that the process is capable of cooking a fish partly embedded inside a block of ice.

RF heating technology is, however, still in its infancy, and a lot of information is currently required to heat each individual food on a plate. As of now, one advantage the microwave has over RF heating is its simplicity, which merely requires turning a dial or punching in a desired time to reheat food. RF heaters need specific numbers and conditioned dialed-in to match a food item’s exact recipe. The diversity among food currently makes cooking the most complicated RF application. Even something like a food’s positioning on a plate needs to be considered when preparing an RF heater, since a food’s placement relies heavily on how the device’s inverters are utilized.

One way to try and simplify the process of RF heating devices preparing different foods are manufacturers and chefs creating recipes for these devices, also figuring out factors like portions and units of measurement expressed in calorimetry or joulemetry. One term that’s been created for joules is “gourmet units.” Going back to the zucchini, veal, and tomato plate—when a cook is preparing the dish, they would dial in individual gourmet units required to properly cook each individual food. The dialog oven would then adjust the units as the device measures the amount of energy required to individually cook each food.

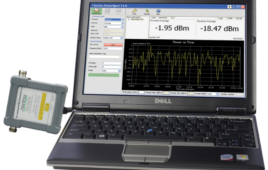

Semiconductor developers are looking to make this process more seamless in time for when these devices begin appearing in people’s homes by focusing on power measure. The amount of power going into the RF heater’s cavity is measured, along with how much power is returned as used energy, which helps approximate the total amount of energy being absorbed. Additional facets like weight, humidity, and temperature may serve as supplementary information when determining the perfect level of “doneness” for the individual foods of each dish.

RF heaters are far from ubiquitous, as individual units currently cost upwards of $10,000. Dr. Werner mentioned at the 2017 Smart Kitchen Summit that prices will drop, similar to the cost of flat screens. Dr. Werner believes prices could drop by 80 percent over the next 2-3 years, which is when we’ll start to see more of these devices appear in people’s kitchens.