A telescope has yielded breathtaking, technicolor images of the night sky, showing what the universe would look like if humans could see in radio waves.

Since 2013, the GaLactic and Extragalactic All-sky MWA (GLEAM) survey has produced a catalog of 300,000 galaxies, captured by Australia’s Murchison Widefield Array (MWA)—a $50 million radio telescope that observes radio waves (some of which have been traveling through space for billions of years) at frequencies from 70 to 230 MHz.

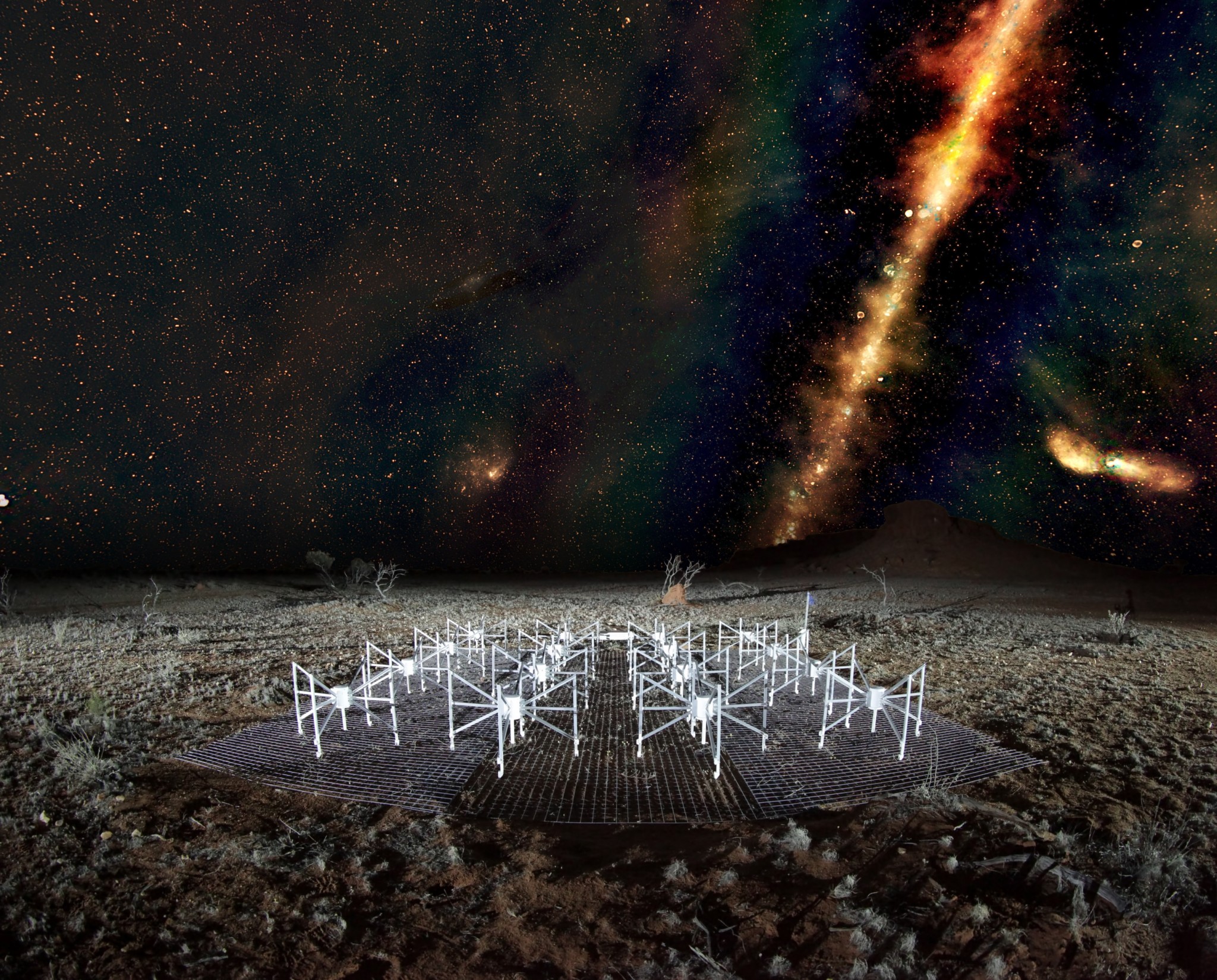

A “radio color” view of the sky above a “tile” of the Murchison Widefield Array radio telescope, located in outback Western Australia. The Milky Way is visible as a band across the sky and the dots beyond are some of the 300,000 galaxies observed by the telescope for the GLEAM survey. Red indicates the lowest frequencies, green the middle frequencies and blue the highest frequencies. (Credit: Radio image by Natasha Hurley-Walker (ICRAR/Curtin) and the GLEAM Team. MWA tile and landscape by Dr John Goldsmith/Celestial Visions.)

While the human eye can only compare brightness in three colors (red, green, and blue), GLEAM views the sky in 20 primary colors.

“That’s much better than we humans can manage, and it even beats the very best in the animal kingdom, the mantis shrimp, which can see 12 different primary colors,” said Dr. Natasha Hurley-Walker from the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR).

The researchers behind the survey, which was recently published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, say the goal is to shed some light (no pun intended) on what happens when galaxy clusters collide.

“We’re also able to see the remnants of explosions from the most ancient stars in our galaxy and find the first and last gasps of supermassive black holes,” added Dr. Hurley-Walker.

The MWA radio telescope is the first of several Square Kilometer Array (SKA) telescopes, which will be built in Australia and South Africa over the next few years. Eventually, SKW will form a single telescope, comprising tens of thousands of antenna.

“By mapping the sky in this way we can help fine-tune the design for the SKA and prepare for even deeper observations into the distant Universe,” said Dr. Randall Wayth, MWA director.

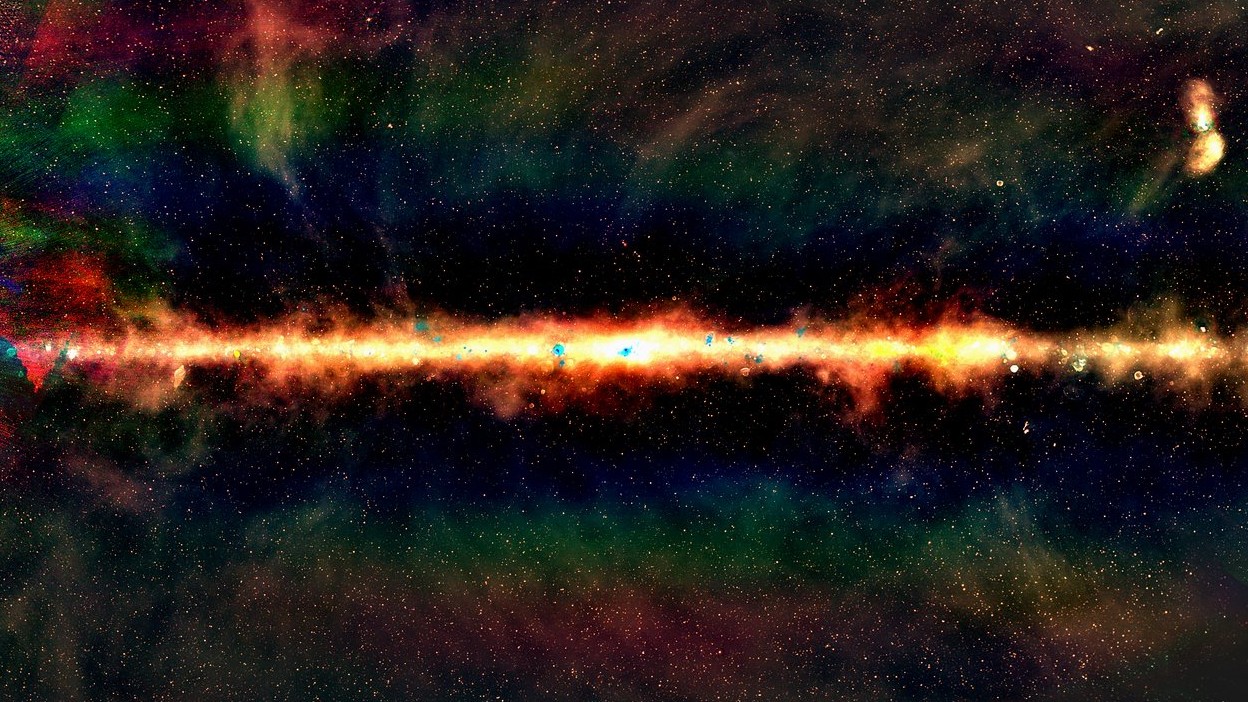

The GLEAM view of the center of the Milky Way, in radio color. Red indicates the lowest frequencies, green the middle frequencies and blue the highest frequencies. Each dot is a galaxy, with around 300,000 radio galaxies observed as part of the GLEAM survey. (Credit: Natasha Hurley-Walker (ICRAR/Curtin) and the GLEAM Team.)